Every year since 2017, we have given our predictions for the greatest threats facing the world. If some of the top risks this year seem to echo those we anticipated for 2025, it is not that they are static, but that the peril continues, without reaching a denouement. The risks of a Trump presidency we feared have come faster and thicker than we envisioned of Gaza, Ukraine, and climate. China and Taiwan are not among the top geopolitical risks, as we judge 2026 is unlikely to see tensions rise to that level in the aftermath of the summit between U.S. President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping.

The world remains in a protracted interregnum, still unsettled, fragmenting, but no less contested. The National Security Strategy makes the U.S. retreat from primacy official: “The days of the United States propping up the entire world order like Atlas are over.” The old neoliberal rules-based architecture is decomposing, power diffusing, and much of the world is searching for new multilateral arrangements to act as a buffer against three predatory, revisionist major powers.

Their efforts raise the question of whether it is possible to have a stable multilateral system without a hegemon. The world is approaching an inflection point, where discontinuity—war, financial crisis, or natural disaster—buries the post-Cold War era and ushers in a new, unknowable order.

With three years yet in his term, Trump is already the most consequential and transformative president since FDR, what some would call a world-historical figure—one who alters the course of history, and likely not for the better. The United States appears to many a predatory rogue actor, a major destabilizing force with Trump diminishing the value of alliances and multilateralism that have been the hallmarks of U.S. foreign policy since 1945.

The militarization of U.S. cities; dissolution of U.S. soft power (e.g., the U.S. Agency for International Development, Voice of America); the slashing of research and development budgets, the secret sauce of U.S. innovation; and abandonment of U.S.-led multilateral institutions (of late, the COP30 climate summit and G-20) and reordering of global trade have fostered worries of a rogue America out to destroy itself and the system it created. Trends are not pointing toward others picking up the pieces, able to renew a rules-based liberal, multilateralist order.

This ninth edition of our annual foresight exercise, “Top 10 Global Risks,” is drawn from our forecasting experience at the National Intelligence Council. In the language of intelligence, we have medium to high confidence in all the probabilities we have assigned to each of the risks, given the “credible” to “high-quality” level of information that is available. As it is for intelligence estimates a “high or medium confidence” judgment still carries the possibility of it being wrong.

1. Trump’s Economic Morass

A banner displayed by the organization MoveOn in Los Angeles on Dec. 12, 2025, protests U.S. President Donald Trump’s tariffs on imports.Patrick T. Fallon / AFP via Getty Images

Many economists have already sounded the alarm that all the preconditions are present for economic meltdown. Financial assets are massively overvalued with unbounded artificial intelligence fueling 40 percent of U.S. GDP growth and 80 percent of stock market growth even though productivity gains by companies experimenting with AI are so far elusive.

Some experts are beginning to doubt whether AI can really go beyond machine learning to the artificial general intelligence of Silicon Valley dreams, charging that current AI models can handle simple problems but “fundamentally break down on complex tasks,” thinking less, not more, as the difficulty rises. A stock market crash could wipe out $35 trillion in consumer wealth, according to former International Monetary Fund Deputy Director Gita Gopinath. Institutionalizing, yet lightly regulating, cryptocurrency adds risk uncertainty.

Adding to these risks is the growing role played by unregulated non-bank financial institutions or shadow banks in corporate finance, and in state finance in China, making it difficult to know how much companies are leveraged. An internal probe of First Brands, an auto parts maker that filed for bankruptcy in 2025, examined how it used money that was due from customers to borrow from lenders several times over. First Brands’s collapse was also spurred by the growing weakness of middle-class consumers no longer able to maintain or purchase new vehicles.

The situation is frighteningly reminiscent of what happened in 2007-08, when the holders of cheap mortgages could not keep up their payments. The K-shaped economy, with just the wealthiest 20 percent of U.S. households fueling consumption, is not sustainable. Tariffs are beginning to increase inflation, and low hiring levels have led to an affordability crisis. Trump has few solutions beyond eliminating his own tariffs on food items such as coffee, negotiating with Big Pharma to lower drug costs, and promising $2,000 checks for most Americans that would boost U.S. debt already equaling around 125 percent of GDP, a level unprecedented for peacetime.

A financial crisis this time around could be far more lethal for U.S. power in the world than in 2008. China and the G-20 are unlikely to help a second time. The U.S. dollar, already weakened, would not be the shield it has been without the U.S. taking drastic action to cut spending and raise taxes.

Probability of crisis:

2. The Dissolution of Order

Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (lower middle) poses with world leaders during the BRICS summit in Rio de Janeiro on July 7, 2025.Mauro Pimentel/AFP via Getty Images

Italian Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci summed up the 1930s with his famous phrase, “The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born: now is the time of monsters.” It’s a description apt for the interregnum between today’s dying liberal order and whatever is to come. It’s not just Trump trashing the ancien régime: Most of the other great powers are out to kill it.

Russian President Vladimir Putin was first out of the gate, waging war on Ukraine to reassert Russia’s interests against NATO. Claiming regional dominance, Xi wants to avenge China’s past century of humiliation, while the global south seeks a greater decision-making role for itself in global affairs. Europe appears paralyzed by its nostalgia for the liberal order, but Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Trump’s weakening of U.S. security guarantees as stated in his recent National Security Strategy are forcing Europe to arm itself for a realpolitik world.

Yet for many states, multipolarity is the answer. Even U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has admitted that it is inevitable, but there is no plan to ensure the global commons is protected at a time of rising extreme poverty and conflict along with growing climate change impacts.

Just like the global economy, multilateralism is fracturing, with the Trump administration exiting the United States from U.N. organizations such as the World Health Organization and defunding others like the World Food Program by its foreign assistance cuts.

Russia and China are expanding alternative organizations such as BRICS to de-dollarize and create alternative currency systems to the U.S. dollar. The mix of diminished institutions and great-power competition points to a deficit of needed cooperation when the next global pandemic, climate, or financial crisis erupts. Domestically, the discontent is even greater, with inequality growing and Western publics irate that globalization appeared to benefit everyone else.

Young people everywhere are seeing the ladders to the good life being kicked away, with populists seeking simple answers in a complicated, fast-changing world. However powerful they are, both states and individuals see themselves as victims. Xi has publicly complained about U.S. suppression and encirclement in an attempt to thwart China’s rise. Putin blames the U.S. and West for starting the war in Ukraine with NATO enlargement, coupled with U.S. efforts to fuel color revolutions in post-Soviet states and never-ending sanctions. Trump and other U.S. leaders have blamed China for cheating on trade, stealing U.S. intellectual property, and foisting COVID on the rest of the word. Gramsci’s interregnum ended with one of the deadliest wars ever. Such an eventuality can’t be ruled out, but for the moment, Trump and other leaders remain fearful of a slide into major state-on-state war.

Probability of crisis:

3. U.S. Pivot to Western Hemisphere

A Trinidad and Tobago Coast Guard speedboat patrols with the USS Gravely warship near the capital of Port of Spain on Oct. 26. Martin Bernetti/AFP via Getty Images

Trump asserted his own corollary to the Monroe Doctrine in his National Security Strategy, pairing it with his threats against cartels in Mexico and regime change in Venezuela—and steep tariffs and sanctions against Colombia and Cuba may be next.

Seeking to establish a dominant sphere of influence in the Western Hemisphere, while sidelining the United States’ other regional commitments, has most Washington strategists scratching their heads. Certainly, the U.S. has ignored its neighbors for too long, but a mix of tariffs, threats, handouts to friendly leaders, and gunboat diplomacy can’t turn the clock back to the 19th century, when the United States was unrivaled in its hemisphere.

China understands better what Latin America wants: economic development. Despite worries about Chinese goods displacing local industries, trade between China, Latin America, and the Caribbean has “soared from $12 billion in 2000 to $315 billion in 2020, with projections indicating it could surpass $700 billion by 2035.” Brazil’s trade with China exceeds “its trade with the U.S. by more than two to one.”

It might have been a different story if President Bill Clinton’s Free Trade Area of the Americas had come to fruition. Instead, Trump has pursued “America First” measures that often backfire, such as cuts to foreign assistance in his first term to Central America that fueled more migration. With the recent food aid cuts, Venezuela and Colombia—two of the biggest Trump targets—“now face even more severe crises—with ripple effects on U.S. farmers, trade, and counternarcotics efforts.”

The risk is that in four years, most Latin American states will have distanced themselves from Washington and moved even closer to China. In focusing too much on Latin America, the U.S. will ignore its other interests and allies. Should Trump put troops on the ground in Venezuela to topple President Nicolás Maduro, the U.S. could get trapped in an escalating military engagement that would be unpopular at home. Blocking Venezuela’s oil exports—the lifeblood of its economy—will likely lead to Maduro’s downfall and to rampant inflation and shortages of food and other essentials, devastating the poor and middle classes. Trump appears to have no plan to help Venezuelans cope with the political instability should Maduro be ousted.

Probability of crisis:

4. Third Nuclear Era

Two Iran-made ballistic missiles are displayed at Azadi Square in western Tehran on Feb. 10, 2025. Morteza Nikoubazl/NurPhoto via Getty Images

2026 begins with the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ Doomsday Clock moved to just 89 seconds to midnight. Great-power competition is driving new nuclear risks, as existing powers such as the United States, Russia, and China seek to increase their stockpiles or carry out new tests, while at the same time, proliferation threats, from Iran to Japan, are unfolding in a third nuclear era.

AI, offensive cyber, and anti-satellite weapons are creating new vulnerabilities for nuclear powers. Gone is the Cold War-era balance of terror, as is the post-Cold War stasis, and its aftermath, when the U.S. and Russia pledged to reduce their nuclear weapons stockpiles by more than 80 percent. The architecture of arms control accords has unraveled. Its last vestige, the New START Treaty, which limits the United States and Russia to 1,550 deployed warheads, expires in February, its fate uncertain.

In a nascent triangular arms race, U.S. military strategists are thinking the unthinkable: to fight two nuclear wars simultaneously. The U.S. is modernizing all three legs (land, sea, air) of its nuclear triad at an estimated cost of $1.7 trillion. Russia is also modernizing its nuclear forces, deploying new short-range “non-strategic” nukes, as is China. The Pentagon says Beijing will have 1,000 nuclear warheads by 2030. In response to Russian and Chinese tactical nukes, the U.S. has developed its own short-range nuclear cruise missiles.

Though the major nuclear powers have not tested nuclear weapons since 1996, Trump has ordered new nuclear tests if others such as Russia and China test. China is expanding its test site at Lop Nur. Moscow’s threats of tactical nuclear use in Ukraine, a lowering of the nuclear threshold, suggested the feasibility of limited nuclear war. This risk extends to lesser nuclear states—North Korea, which has massively built up its missile and nuclear force capabilities, and India and Pakistan, whose nuclear rivalry continues.

Faced with volatile security predicaments in the Middle East and East Asia and doubts about U.S. reliability, recent U.S. deals—nuclear submarines for South Korea, a U.S.-Saudi civil nuclear program—raise concerns. Both may involve reprocessing nuclear fuel with which they could join Japan as virtual nuclear powers. South Korea js debating the virtues of nuclear weapons, and Japan is also rethinking its nuclear allergy. What could go wrong?

Probability of crisis:

5. Gen Z Rebellion

Security forces intervene against Generation Z protesters in Antananarivo, Madagascar, on Oct. 9.Rafalia Henitsoa/Anadolu via Getty Images

Generation Z, a demographic cohort born between 1997 and 2012 that constitutes 20 percent of humanity, faces a future challenged by an unraveling global system. Gen Z is concentrated in the Global South. In South and Southeast Asia, one-third or more of the population is less than 25 years old; in Africa, almost 60 percent of the population (some 890 million people) was less than 25 years old in 2024. The continent’s median age was 19.3 years in 2025.

Disillusioned by internet censors, government corruption, and a jobs deficit, Gen Z is already wreaking havoc on governments in Africa and South and Southeast Asia. Since 2024, a tsunami of youth-led protests has brought down governments in Bangladesh, Madagascar, and Nepal; caused other states such as Indonesia, Kenya, and Morocco to dismantle unpopular policies; and spurred brutal repression, as in Tanzania. Across the Middle East, the political impact of “youth bulge”—under-25-year-olds constituted 60 percent of the region’s population in 2025—grows, although it has not yet triggered a new Arab Spring or another burst of protests in Iran. Gen Z protests in Bulgaria in December that unseated its government suggest the West may not be immune.

Africa’s predicament is even worse. The region contains 20 of 39 states the World Bank dubbed fragile or conflict affected in fiscal year 2026. These countries are replete with internal clashes, ranging from civil wars to terrorist attacks. All have large unskilled youth bulges with few employment opportunities. On a more basic level, almost 600 million sub-Saharan Africans lack access to electricity.

African states are also heavily burdened by foreign debt—$746 billion cumulatively. And government debt in sub-Saharan Africa averages around 60 percent of countries’ gross domestic product. Approximately 57 percent of Africans live in countries that spend more on external debt servicing than education or health care.

These youthful nations must find a path to development amid what some have dubbed a global polycrisis—a cascading set of intersecting problems. Those challenges include a growing North-South economic and technological divide; declining aid; and navigating global financial negotiation to manage deepening debt issues, climate change, food insecurity, disease, and (not least) the risks to jobs from artificial intelligence.

As the Gen Z drama unfolds, its impact will ripple across the world—whether resulting in prosperity, where governments find the means to educate and employ this cohort; or, where they do not, poverty, terrorism, disease, civil wars, and mass migration.

Probability of crisis:

6. An Empowered Putin After Ukraine

Russian President Vladimir Putin shakes hands with Trump at the end of a news conference in Anchorage, Alaska, on Aug. 15, 2025. Andrew Harnik/Getty Images

Conventional conflicts such as the Russia-Ukraine War, if not resolved in the first year, on average tend to last more than a decade unless they transform into a frozen conflict or reach a cease-fire. But after three years of war, Russia increasingly has the upper hand and appears unlikely to settle without forcibly taking the Donbas or being given the region in a peace agreement.

The Europeans alone are not capable, nor is the United States under President Donald Trump willing, to provide Ukraine with the arms that could give it a fighting chance. Peace negotiations have been a never-ending merry-go-round, with Trump agreeing to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s terms before pushing them on Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, who musters European support for refusing them.

The recent U.S. National Security Strategy targets Europe, forecasting “civilizational erasure” for the continent and blaming it for Ukraine’s resistance to a cease-fire. So far, Putin has not moved an inch to water down his terms. In the worst case, Trump will tire and dump the Ukraine problem on the Europeans, who won’t be able to turn the tide and don’t have much influence with the Kremlin.

With Russian forces advancing into Ukraine, Putin could become even greedier and less interested in settling. Russia is reportedly stockpiling long-range missiles that could devastate Ukraine. At best, Kyiv would impede a complete victory for Moscow, but it can’t achieve a just peace without strong support from a united NATO. A peace settlement that endures and averts another conflict needs strong support from the United States. And although Trump says he wants a cease-fire, his real goal appears to be bilateral trade and investment deals with Russia. With U.S. and European leaders at loggerheads, Russia appears to have achieved its long-term goal of splitting the West and emasculating NATO.

Probability of crisis:

7. Climate Decline

Morning smog clouds the view at Kartavya Path in New Delhi on Dec. 14, 2025.Vipin Kumar/Hindustan Times via Getty Images

As climate change worsens, there is a serious risk of weakening countermeasures—and poorer countries, already hurt the most, will bear the brunt of the impact. U.S. opposition to climate efforts is also ceding leadership to China.

Trump called climate change “the greatest con job ever perpetrated on the world” in his address to the U.N. General Assembly in September. Not only did he withdraw the United States from the 2015 Paris Agreement for the second time, Trump has pressed other countries to drop their climate efforts and concentrate on exploiting more fossil fuels.

To some extent, this has worked. Inside the United States, many companies are scaling back their earlier promises to fight climate change, and Microsoft founder Bill Gates wrote a remarkable memo that downgraded climate change’s place in his philanthropic foundation’s objectives list. There was no mention in the 2025 U.N. Climate Change Conference final statement of fossils fuels, much less a roadmap thanks to Russia, Saudi Arabia, and other oil producers blocking one. And with China staying silent, the European Union showed itself ineffective in countering these anti-climate efforts.

The EU’s silence “partly reflects the power shift in the real world,” one analyst told the BBC, linking the emerging power of the Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa coalition to the decline of the EU. Even within the EU, there are concerns that meeting its aggressive 2040 emissions reduction target will aggravate the group’s weakening economic competitiveness.

At the U.N. climate conference, the goal of $120 billion a year in climate financing for poor countries was pushed back five years, from the initial suggested date of 2030 to 2035. This increases the climate risks for poorer countries already highly vulnerable to droughts, floods, and higher temperatures inhibiting agricultural production and spreading disease. Meanwhile, the World Meteorological Organization forecast a 70 percent chance that five-year average warming for 2025-29 will be more than 1.5 degrees Celsius (up from a 47 chance for 2024-28 in last year’s report).

China’s transformation into a renewables giant is the only positive note on climate this year. The country accounts for 74 percent of all large-scale solar and wind capacity under construction, compared to 5.9 percent for the United States. Not missing an opportunity, China has capitalized on wind, solar, and battery technologies, which constituted more than a quarter of its economic growth in 2024.

Probability of crisis:

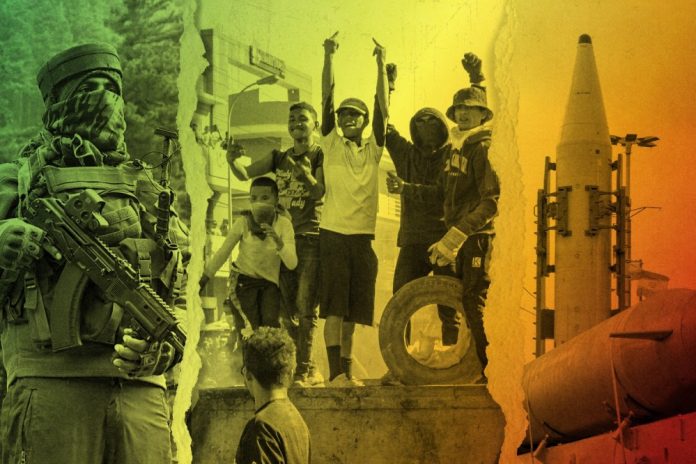

8. A Persistently Dangerous Middle East

Israeli soldiers stand near military vehicles close to the border with the Gaza Strip in southern Israel on Sept. 17, 2025.Amir Levy/Getty Images

Despite hopes yet again for a “new Middle East,” the region’s most enduring problems—Gaza and Iran—may move closer to renewed conflict than peace in 2026. The United States, mired in both conflicts, and with new security commitments to Saudi Arabia and Qatar, is deepening its entrenchment in the region despite vowing in the new National Security Strategy to narrow its interests.

The first phase of the Trump-designed cease-fire plan for Gaza is already getting mugged by reality. Gaza is de facto partitioned, with Israel controlling more than half of the territory and most Palestinians living in ruins in the other half. Meanwhile, Hamas is refusing to disarm and has reasserted its military and political presence. Fighting continues to flare up from both sides.

There are indications the United States is considering redeveloping the Israeli-controlled half of Gaza. These realities impede further implementation of the peace plan, elements of which include an international stabilization force and a transitional, technocrat-run Palestinian administration.

In the West Bank, Israeli settler violence and military operations continue to fuel tensions. Getting to the second phase of the Gaza peace plan and charting a “credible pathway to Palestinian self-determination and statehood” appears distant.

Other destabilizing factors in the region are Israeli attacks on Lebanon, meant to prevent a resurgence of Hezbollah, and Syria, threatening the country’s political transition. And Iran, facing chaos and potential renewed war, may be an even more explosive risk. The country’s economy is cratering due to intensified sanctions over its nuclear program. Tehran is also facing a water crisis after five years of drought and mismanaged agricultural and economic policies. Iran’s president warned in November that Tehran might need to be evacuated if the drought continued. These predicaments are compounded by an ailing, often absent, 86-year-old supreme leader, Ali Khameini, whose power is waning. The line of succession is uncertain—and could spur unrest or a coup by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.

Against this backdrop, the International Atomic Energy Agency says Iran still has enriched uranium, despite U.S. and Israeli bombings, and there are signs Tehran is continuing its nuclear program. It reneged on an agreement with the agency to resume external monitoring of its nuclear activities, and it has rejected U.S. offers of renewed nuclear talks (though it hints new talks are possible). Renewed Israeli and/or U.S. bombing of Iran is a looming prospect.

Probability of crisis:

9. Artificial Intelligence: the Great Disruptor

A technician works at an Amazon Web Services AI data center in New Carlisle, Indiana, on Oct. 2, 2025.Noah Berger/Getty Images via Amazon Web Services

The transformational power of artificial intelligence cuts in different directions. On one hand, for example, AI could help detect, treat, and maybe even cure diseases such as cancer, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s in the coming decade; on the other, it could be a new source of social disorder and contribute to democratic demise.

Multiple AI risks are mounting. Most immediately, AI could soon render obsolete many jobs and is already contributing to job losses and hiring freezes. Some CEOs warn that AI could replace half of U.S. white-collar workers. In January 2024, an International Monetary Fund analysis concluded 60 percent of jobs in nations with advanced economies would be impacted by AI, yet there appears little urgency to rethink skills training and education.

But the real problem may be that AI turns out to be much less that promised—or threatened. Even if the technology is transformative in the long run, the short term race for AI dominance poses financial risks that may bite in 2026. The investing boom in the technology is fueling fears of a bubble that will soon burst while much of the rest of the U.S. economy sputters. In 2024, global Big Tech invested more than $400 billion in data centers (of which there are now more than 5,000 in the United States). And that investment is projected increase massively by 2029, to $1.1 trillion (and one prediction expects $2.8 trillion on AI-related infrastructure as a whole). Increasingly, though, this investment is through debt. OpenAI doesn’t expect profits until 2030; Anthropic hopes to break even by 2028.

Nor are many AI pilots reporting return on their initiatives. The gap between massive investment and a dearth of revenues is sparking fears of a crash reminiscent of, if not worse than, the 2000 implosion of the dot-com bubble. There is also a gap between AI energy needs and available electricity, despite newly built power plants, leaving some data centers idle and driving up electricity prices.

Risks don’t end there. Some Americans, including Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang, think that China is winning the AI innovation race. China’s open-source AI approach, as its popular DeepSeek chatbot demonstrated, results in models cheaper and just as effective, though less technologically advanced, than U.S. products. While U.S. AI models seeks superintelligence, China focuses on practical apps. These products may appeal to much of the Global South, which already uses China’s digital infrastructure.

On top of these risks is the concern, as AI founders have voiced, that AI will render humans extinct.

Probability of crisis:

10. A Shaky Asia-Pacific

An Indian paramilitary service member keeps watch in Pahalgam, Kashmir, on April 23, 2025. Tauseef Mustafa/AFP via Getty Images

There are multiple risks in Asia now. But some of the usual suspects (e.g., North Korea) are more conspicuous by their absence in the new U.S. National Security Strategy. While geopolitical uncertainty in East Asia has not diminished, U.S.-China ties are likely to be steady at least through 2026. Beijing’s military coercion of Taipei and in the South and East China seas is unlikely to escalate beyond the threshold of gray zone activities.

Trump’s tariffs and Chinese manufacturing overcapacity pose dual threats to the Asian economy, undermining regional production networks in South and Southeast Asia that are based on a “China +1” strategy—a diversification scheme in which investors move factories out of China but use Chinese components. Though it encouraged such moves during the first Trump administration, the United States is now seeking to cut China out of these supply chains altogether.

Trump has signed trade deals with four member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), but the United States has yet to clarify final tariff levels. They will depend on how Trump decides the rules of origin—guidelines that determine, for instance, whether goods using Chinese components that were processed into final products in Vietnam (or other nations) and exported added enough local value to be tariffed at Vietnamese rates, or if they are designated as transshipped goods facing higher Chinese level tariffs.

Current tariffs are already taking a toll on Asia, but if the United States requires a high level (say, 50 percent or more) of value added to avoid transshipment tariffs, Southeast Asia’s economy could be hit hard particularly if a flood of Chinese surplus goods shuts down ASEAN factories.

The locus of security conflict risks is South Asia. India-Pakistan tensions after recent terrorist attacks highlight a combustible situation. Both sides claimed victory after skirmishes this spring. Meanwhile, Pakistan’s military (and personnel such as Defense Forces Chief Asim Munir) has been emboldened by constitutional changes that enhanced its power.

Munir was bolstered by his diplomatic success in persuading Trump to tilt toward Pakistan and rebuke India, and by Pakistan’s defense pact with Saudi Arabia. In contrast, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi appears weakened by a Trump snubbing. Both leaders have something to prove. The mix of a simmering dispute in the Kashmir region, terrorism concerns, problems with Afghanistan, and water disagreements could relight the fuse.

Pakistan also has to worry about a second front—terrorism, its ongoing clash with Baluchi separatists and the resurgent Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan militant organization. Confrontations with the latter group have spilled over into military clashes with Kabul, and Islamabad is deporting one-third of the 3 million Afghan refugees living in Pakistan across a porous, disputed border.

In short, tensions in the region remain high, with on-off cease-fires, and unresolved issues including simmering India-China border disputes suggest more conflict ahead.

Probability of crisis: