Jafar Panahi sank into his chair against a brick wall and stared into the Zoom call. “It’s like you’re looking at me from the bottom of a well,” he said, half-joking, studying my video feed.

I was supposed to meet Panahi in person for the North American premiere of It Was Just an Accident, his first film since being released from prison in Tehran two years ago. But due to the U.S. government shutdown, his visa didn’t come through in time, so my trip from upstate New York to the city proved pointless, and we had to resort to Zoom. Ever the director, Panahi instructed me to adjust my camera so the right amount of my head and torso was in frame. Only then was he ready to talk.

Jafar Panahi is one of the most celebrated filmmakers alive. Just months before we talked, he’d won the Palme d’Or at Cannes, making him only the fifth filmmaker in history (and the only living one) to win the top prize at all three major European festivals. Yet to many Iranians, Panahi is known as much for his defiance as for his cinema. His political outspokenness and global visibility have long brought him into conflict with the government, which remains uneasy with independent artists. This tension reached a breaking point in 2010, following the Green Movement protests. While Panahi was working on a film with his friend and collaborator Mohammad Rasoulof, security agents raided his home, confiscated their equipment, and hauled them and several others to Tehran’s notorious Evin Prison.

Behind bars, Panahi went on hunger strike, sparking outrage across the international film community. At Cannes, the jury placed an empty chair onstage to highlight his absence. By the end of the year, a court had convicted Panahi of “assembly and colluding with the intention to commit crimes against the country’s national security and propaganda against the Islamic Republic,” and issued a draconian sentence: six years in prison and a 20-year ban from filmmaking, giving interviews, and leaving the country.

Panahi was released after a few months, placed under house arrest, and went on to make several films in secret. In 2022, he was once again arrested and imprisoned, triggering outrage. This time, upon his release seven months later, a judge dropped the charges and lifted Panahi’s outstanding ban. Then Panahi got to work. It Was Just an Accident is the first film he has made in relative freedom in almost two decades.

In the last few months, Panahi has given dozens of interviews while traveling internationally to promote It Was Just an Accident, which has been the subject of much critical acclaim. But little has been said about how it fits into his broader cinematic project. I have followed Panahi’s career closely, watched every movie shortly after it came out, and spent many hours in dorm rooms and cafes in Tehran discussing his work with my peers and friends. This compelled me to view his last film in the context of his body of work as a filmmaker. It Was Just an Accident has unmistakable echoes with Panahi’s earlier work, but it also feels like a departure: a more ambitious chapter from a filmmaker who has spent three decades testing the boundaries of cinema and the limits of expression.

A film still from It Was Just an Accident.Jafar Panahi Productions, Les Films Pelléas, Bidibul Productions, Pio & Co, and Arte France Cinéma

“He who fights with monsters should be careful lest he thereby become a monster,” the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche wrote in his 1886 book, Beyond Good and Evil. “For when you gaze long into the abyss, the abyss also gazes into you.” It’s a fitting summary for It Was Just an Accident.

Vahid, a former political prisoner at Evin, works as a mechanic on the outskirts of Tehran. One evening, a car pulls up outside his workplace, and the driver asks for help. Vahid overhears and recognizes the voice instantly—it’s Eghbal, the man who once tortured him in prison. Although he was blindfolded throughout his interrogations, Vahid remembers the voice, as well as the squeak of the man’s artificial limb.

After the car is repaired, Vahid follows Eghbal home. He kidnaps Eghbal the next day and drives him to a remote spot outside Tehran. He is about to bury the man alive when Eghbal begins to plead, insisting he is not who Vahid thinks he is. Vahid wells up with doubt, uncertain if he has the correct man. So he calls up his fellow former prisoners, two men and two women, who cram into Vahid’s van and set off on a strange odyssey across Tehran to confirm the man’s identity.

None of them are sure, until Hamid comes on board. In prison, Hamid was forced to touch his interrogator’s wounded leg, so when he sees Eghbal, he easily identifies him as the ruthless man who ruined their lives. But confirming the man’s identity turns out to be the easy part. The real question is what to do with him.

The ragtag group of former inmates, who have clashing political persuasions, temperaments, and values, become embroiled in long, sometimes violent debates. Should they let Eghbal go? Kill him? Or would killing their former captor turn them into the very monsters they hope to avenge?

For the last four decades, many Iranians, myself included, have felt that it was easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of the Islamic Republic. But that’s no longer the case. The gap between the Iranian people and their rulers is growing, the economy is in free fall, and corruption is devouring the ruling elite from within. Iran has experienced more nationwide uprisings over the last decade than in the 35 years prior.

For the first time in decades, the question is no longer just how to get rid of this government but what to do with its officials once they are removed from power. This, it seems, is Panahi’s central focus in It Was Just an Accident.

Panahi has lived through much of what his characters endure in the film. During his imprisonment, he spent days in solitary confinement and countless hours in interrogation rooms—blindfolded, seated on a hard wooden chair facing the wall, listening to the breathing and movements of the interrogator behind him.

“Most of the time in the interrogation room was spent on written Q and A,” he told me. “The guy would write a question on a piece of paper, put it in front of me, and I’d write my answer, seeing the page only through the narrow crack beneath the blindfold. But as a filmmaker, I am always attentive to sounds and voices, and I was so focused on what I heard that I could barely write my answers.”

While his interrogator waited for Panahi’s responses, the director found himself trying to construct an image of this man holding him captive. How old was he? What did he look like? What kind of life did he lead outside the prison? Would Panahi recognize his voice if he ever heard it again? What would he do if he did?

When I ask Panahi whether he has an answer for that last question, he shakes his head. He isn’t interested in that kind of speculation. “When I got out of prison, from the second I stepped out, I couldn’t stop thinking about the guys I’d left behind,” he said.

He means it almost literally. In a video of his release from Evin in 2023, Panahi is surrounded by friends and reporters, his back to the prison gate. When asked how he feels, he says, “How can I be happy with all those people still behind that wall?” Panahi spoke for several minutes about the friends he made inside, the lessons he learned, and the solidarity that sustained them.

That spirit hasn’t changed. “All my thoughts and concerns were about doing something for them,” he said. “Making films is the only thing I know how to do. Apart from that, I was also trying to find a way to organize the chaos in my head, to give shape to all the thoughts and feelings I carried with me out of prison.”

“I’m a social filmmaker, and for all those months, those guys were my social life. It was only natural that the people I met there ended up becoming inspirations for my characters.”

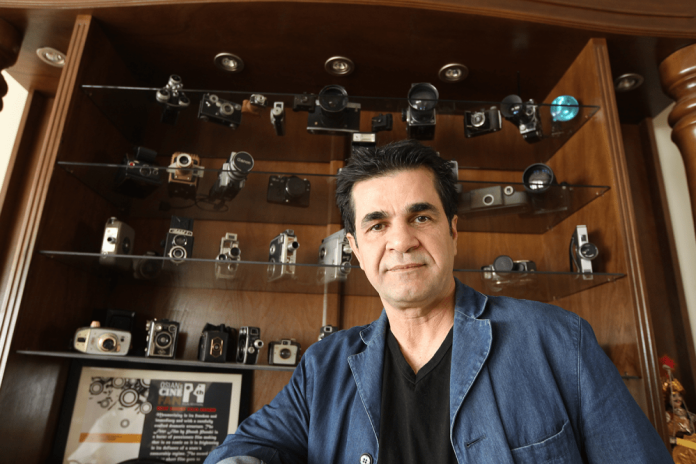

Panahi in Taxi. Jafar Panahi Productions via Kino Lorber

Since the 1990s, Panahi has been a central figure in the post-revolutionary new wave of Iranian cinema. He followed in the footsteps of his mentor, Abbas Kiarostami, the towering figure of global art cinema known for his slow, melancholic films. Panahi adapted this new cinematic language but shifted his focus from the rural landscapes Kiarostami favored to the urban backdrop of Tehran.

Starting with The White Balloon (1995), Panahi has established himself as a leading practitioner of what film theorists call non-cinema—in other words, films that resist the conventions of mainstream cinema. Film scholar William Brown regards non-cinema as a filmmaker’s way of foregrounding what traditional cinema excludes or hides from view—everything that prevents film from becoming a profit-making machine.

Non-cinema films may shoot low-quality images with a cheap camera or insufficient lighting. Their narratives might be nonlinear or feature non-actors in lead roles. Over time, those supposed insufficiencies became a style in their own right, especially for filmmakers in the global south working under technological and political constraints. The resulting style challenges both dominant forms of cinema and the power structures imbedded within them.

Panahi’s film style is a cinema of the poor—not because he often tells stories about working-class and marginalized people, which he does, but because he positions his filmmaking outside the entrenched bond between cinema and capital. “In a world where films are made with millions of dollars,” he once said of The White Balloon, “we made a film about a little girl who wants to buy a fish for less than a dollar—this is what we’re trying to show.”

Panahi’s tendency to feature non-professional actors and narratives that blur the line between documentary and fiction was present in his early films, but it became all but inevitable after his initial imprisonment and the ban on filmmaking that pushed him underground. This Is Not a Film (2011), its title a direct nod to the idea of non-cinema, Closed Curtain (2013), and Taxi (2015), emerged during this period, with Panahi himself often appearing on screen.

In 3 Faces (2018) and No Bears (2022), Panahi went to East Azerbaijan, a province in Iran’s northwest, where he was born. There, he filmed in remote villages far from the eyes of security forces. Yet even these works, conceived as creative ways to evade restrictions, retained a documentarian edge—sense of entrapment that reflected his years of imprisonment.

It Was Just an Accident marks a significant departure from Panahi’s non-cinema approach. Though he is often cited as a leading practitioner of non-cinema, he is ambivalent about the term. He insists that It Was Just an Accident is closer to the kind of film he has always wanted to make. His experiments with non-cinema, he explained, were driven by necessity rather than aesthetic choice—merely ways to keep creating under impossible constraints.

“After the house arrest,” Panahi said, “I was in absolute shock. Everything I did had to involve me somehow, as a way of making sense of my own situation. My friend [Mojtaba] Mirtahmasb came over with a camera, and we started shooting, building a story as we went, and called it This Is Not a Film. Then I began wondering how I would make a living if I couldn’t make movies, and the only thing that came to mind was driving a taxi. But being who I am, I knew I’d put a camera in it, so that idea became a film. In those works, my main concern was to show that there’s always a way out.”

The removal of the ban on Panahi’s filmmaking technically allowed him to finally return to the streets of Tehran to film without fearing a raid on his set. Still, he would have to submit his script to the Ministry of Culture—essentially a censorship office—and procure a license for shooting. The story he wanted to tell would never pass the censors, so he filmed it underground instead.

In the absence of direct pressure and constant surveillance, Panahi no longer felt the need to appear as a character or to make the act of filmmaking a central theme. That shift allowed the camera to shed the self-reflexivity that defined so many of his previous films. Instead, Panahi settled into the classical role of the filmmaker. “In making It Was Just an Accident,” he said, “for the first time in years, I got to return to where I’ve always wanted to be: behind the camera.”

A film still from It Was Just an Accident.Jafar Panahi Productions, Les Films Pelléas, Bidibul Productions, Pio & Co, and Arte France Cinéma

In Taxi, a young film student asks Panahi, playing a taxi driver, for advice. He is struggling to come up with an original idea for his final project. Despite having watched countless films and read many books, he’s stuck. “Those stories are already written, those movies are already made,” Panahi’s character tells him. “You’ve got to get out of the house.”

It’s a fitting piece of advice that resonates throughout Panahi’s body of work. In his films, characters rarely stay indoors. They are constantly in motion—running like the little girl in The White Balloon, walking like the women in The Circle (2000), riding a motorcycle like Hossein in Crimson Gold (2003), or driving through the streets like the characters in It Was Just an Accident. Panahi’s characters never have the luxury of leisurely observation. They are always in pursuit of something urgent, often as a matter of survival.

It’s difficult to think of another Iranian filmmaker whose work so vividly charts the evolution of Tehran itself—its shifting architecture, its social tensions, its light and noise. Watching his films from the 1990s to today is like watching Tehran grow both older and younger, more crowded, more wounded, and more alive.

In It Was Just an Accident, we see a new Tehran, reshaped by the 2022 Woman, Life, Freedom movement, since which many women no longer abide by compulsory hijab rules. The film unfolds mostly from inside a van, the city glimpsed through windows. Still, its transformation is unmistakable. For those of us in exile who haven’t returned since that uprising, seeing the women characters without the hijab is electrifying, especially when contrasted with Panahi’s earlier films.

Panahi told me he never so much chose to shoot outdoors as being pushed there. Part of it came from his obsession with capturing urban reality in its most authentic form. But the constraint of the compulsory hijab was a larger factor, since filmmakers are prohibited from showing women without one onscreen. “A woman sitting in her room wearing a headscarf—it’s just not believable,” Panahi said. “Forget about censorship. It destroys the believability of the movie.”

In many ways, Iranian cinema has always thrived on these obstacles. What seemed like a seemingly insurmountable restriction gave rise to an aesthetic innovation, and over time, those workarounds became the foundation of a distinctive cinematic language. Panahi’s films are a testament to this—born out of necessity, yet charged with the urgency of a filmmaker determined to capture a changing world within extremely difficult circumstances.

Panahi has always insisted that he is not a political filmmaker but a social one. To him, political cinema carries preconceived notions about characters based on their beliefs, set within a framework where good and evil are easily distinguishable. Social cinema, by contrast, is not interested in characters with clear-cut morality.

Yet, in the Iranian context, Panahi’s films inevitably carry political weight. There’s a common thread running through his body of work: the powerless striving to gain power. Panahi’s characters relentlessly search for small ways to manipulate the system, bend the rules, and carve out space for themselves in a society that leaves little room for freedom. None has the power to stage a rebellion. Their resistance is quieter, more intimate. They talk their way into places where they are not welcome, or out of situations in which they are trapped. They drag their feet at work, sabotage petty injustices, or break laws in minor yet meaningful ways. In a country where the boundaries of permissible behavior are narrow and the faintest hint of collective dissent is crushed, such small gestures take on outsized significance.

Panahi’s cinema is full of these moments: the women smoking—an act policed in public life—in The Circle; the little girl in The Mirror (1997) who tears the fake cast off on her arm, looks into the camera, and declares she doesn’t want to act anymore; the young women in Offside (2006) sneaking into Tehran’s Azadi Stadium to watch a soccer match; the girl in 3 Faces who fakes her suicide to lure a famous actress to her remote village and secure a path to university.

After his first imprisonment, when he was under house arrest, Panahi extended that same spirit of resistance to his own career. The simple act of making This Is Not a Film, which was smuggled out of Iran on a flash drive, became both an artistic and political statement—declaration that even within confinement, creation and defiance are possible.

In It Was Just an Accident, the table is turned. For the first time in Panahi’s cinema, the powerless gain the chance to subjugate the powerful. By sheer coincidence, the captor becomes captive, and the torturer finds himself at the mercy of the tortured. In this sense, the film may mark a new phase in Panahi’s career. His lifelong concern has been to show how the oppressed carve out space for resistance in a repressive system. Here, he poses a more unsettling question: What if those who were dominated now hold the means to dominate? Or, to put it in political terms, what might the world after the Islamic Republic look like?

“In interviews, I’m constantly asked about revenge and forgiveness and all that,” Panahi told me. “But those aren’t my concerns here. … What I’m really thinking about is the future. The question I ask is this: Will this cycle of violence continue? Are we going to execute everyone who worked for this regime and end up in the same hole again? That’s my question.”

Not that he is neutral: Panahi is careful to keep his political preferences out of his latest film, but he has made clear his commitment to nonviolence and his admiration for practitioners of it, including his fellow Evin prisoners Farhad Meysami, the political activist known for his near-death hunger strike experience, and Saeed Madani, the sociologist who held walking lectures about the history and principles of nonviolence for other inmates in the prison courtyard.

The question Panahi poses about the future is on the minds of many Iranians, no matter their political beliefs. It is a hard question, if only because it is rooted in hypotheticals, yet urgent all the same. To begin to answer it requires an active, collective imagination, a willingness to think together about what justice might mean before it is too late.

Cinema, at its best, can be a tool for that kind of shared reflection. And Panahi, who has kept his finger on the pulse of Iranian society for more than three decades, is uniquely positioned to help do that, especially if he is allowed to return to where he has always wanted to be: out on the street, behind the camera.

That is a big “if” in Iran today. Indeed, earlier this month, the Iranian authorities sentenced Panahi in absentia to one year in prison and a two-year ban on travel outside Iran over his supposed “propaganda activities.”

This hasn’t rattled Panahi. When asked about the new sentence, he indicated that he would return to Iran after wrapping up his Oscar campaign next year. “I have only one passport. It is the passport of my country, and I wish to keep it,” he said at the Marrakech International Film Festival on Dec. 4. “My country is where I can breathe, where I can find a reason to live, and where I can find the strength to create.”

Tehran isn’t shy about using maximum force and naked violence to silence dissent among the general population. But against someone like Panahi—an internationally celebrated artist—it wages a war of attrition. He is repeatedly summoned, banned from filmmaking or traveling, jailed for a few months here, a year there. For most people, this strategy works. It exhausts them into surrender.

Panahi has proved unusually resilient. Each time he is arrested, he emerges louder and braver. Each time he is barred from making films, he makes one underground, sharper and more scathing than anything that came before. In this 20-year marathon between Panahi and the Islamic Republic, he has outlasted many judges and interrogators. This time will be no different.