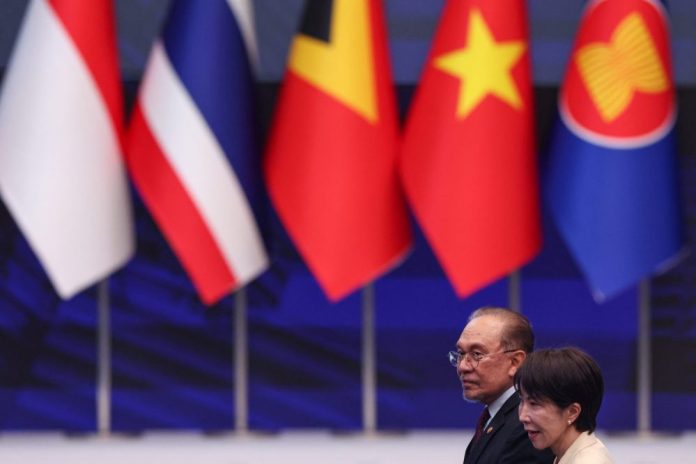

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is often dismissed as little more than a talk shop—long on meetings and statements but short on concrete action. As I have previously argued in Foreign Policy, the bloc has generally suffered from policy paralysis since its inception in 1967, mainly because of disunity among members over collective security actions to address challenges across Southeast Asia. This assessment, however, needs an update: In recent years, the 11-member group has increasingly striven to match its words with deeds—probably due to rising threat perceptions, stronger leadership, and greater pressure from U.S.-China competition that is pushing ASEAN to act to avoid irrelevance.

The latest example involves Cambodia and Thailand, two ASEAN members that have been locked in border disputes for many decades. During U.S. President Donald Trump’s visit to Malaysia last month for the annual ASEAN summit, he also presided over a peace signing ceremony that officially ended hostilities between Phnom Penh and Bangkok over the disputed Preah Vihear temple and surrounding areas. But a fresh round of violence has put these two countries back on edge. On Nov. 10, four Thai soldiers were wounded by a land mine, followed by an exchange of gunfire that led to the death of one Cambodian villager. Bangkok blames Phenom Penh for recently planting the explosive device, while the Cambodian government claims it was left over from past wars.

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is often dismissed as little more than a talk shop—long on meetings and statements but short on concrete action. As I have previously argued in Foreign Policy, the bloc has generally suffered from policy paralysis since its inception in 1967, mainly because of disunity among members over collective security actions to address challenges across Southeast Asia. This assessment, however, needs an update: In recent years, the 11-member group has increasingly striven to match its words with deeds—probably due to rising threat perceptions, stronger leadership, and greater pressure from U.S.-China competition that is pushing ASEAN to act to avoid irrelevance.

The latest example involves Cambodia and Thailand, two ASEAN members that have been locked in border disputes for many decades. During U.S. President Donald Trump’s visit to Malaysia last month for the annual ASEAN summit, he also presided over a peace signing ceremony that officially ended hostilities between Phnom Penh and Bangkok over the disputed Preah Vihear temple and surrounding areas. But a fresh round of violence has put these two countries back on edge. On Nov. 10, four Thai soldiers were wounded by a land mine, followed by an exchange of gunfire that led to the death of one Cambodian villager. Bangkok blames Phenom Penh for recently planting the explosive device, while the Cambodian government claims it was left over from past wars.

Regardless, ASEAN, through its Malaysian chair for this year, has stepped in to deal with the escalating situation. The group quickly deployed an observer team to probe the incident and to inspect land mines in the area. The observers delivered a useful finding: The land mine indeed had been newly placed, though thus far they have not (and probably won’t) assign blame to either party. Nonetheless, through this ongoing operation, ASEAN has demonstrated that it can assemble a coalition of its members to provide real-world value toward maintaining peace and stability in Southeast Asia.

Another example of ASEAN finally having some skin in the game pertains to another fellow member, Myanmar. In February 2021, a military junta overthrew the civilian-led government, prompting mass protests that eventually devolved into a civil war that rages to this day. Brunei, which chaired ASEAN at the time of the coup, began pressing for a resolution. The bloc came up with the so-called Five-Point Consensus, which called for an immediate cessation of violence, constructive dialogue among all parties, the appointment of a special envoy to facilitate mediation, ASEAN humanitarian assistance, and the envoy’s visit to Myanmar to meet all parties.

To be sure, ASEAN has yet to leverage its consensus to resolve Myanmar’s civil war—and this may never happen. Regardless, it is noteworthy that the consensus wasn’t merely rhetoric but also included several concrete action items. Since ASEAN forged the agreement, it has sought to meet its own standards for action. The ASEAN Coordinating Centre for Humanitarian Assistance, for instance, has attempted to deliver aid but has been constrained by a lack of funding. ASEAN has sent its envoys to Naypyidaw to hold negotiations with the junta and civilian government, but they have not made much progress, not only because of the regime’s obstinance but also because of a lack of cohesion among ASEAN members. Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand have broken ranks and engaged Myanmar bilaterally outside of the ASEAN mechanism. Although collective efforts have been unsuccessful to date, the bloc has shown an uncharacteristically high appetite for rolling up its sleeves to get things done rather than sitting in conference rooms to hold endless negotiations lacking teeth.

It remains unclear whether ASEAN will continue to play a proactive role in regional disputes and whether its efforts will be more successful in the future. Through 2026, at least, this prospect is quite likely because the Philippines as the group’s next rotating chair hopes to hammer out a collective security response to China’s ongoing encroachments in the South China Sea. Of late, Manila has been at the forefront of criticizing Beijing’s increasingly assertive behavior in the region, highlighted by its rising use of gray-zone tactics to threaten the Philippines and secure its vast territorial claims, including in the exclusive economic zones, or EEZs, of the Philippines and other Southeast Asian countries. This has prompted Manila to reaffirm a July 2026 deadline for ASEAN and China to conclude their decades-long negotiations over a legally binding code of conduct in the South China Sea. This document would seek to legally prevent aggressive behavior and mandate the settling of disputes on the basis of international law and norms as codified by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

It is unlikely, however, that Manila will fully benefit from ASEAN’s recent proactive mood. This is because certain members, particularly Cambodia and Laos, are less vested in the outcome of the South China Sea dispute; these two countries also maintain close strategic partnerships with China that enable Beijing to exert pressure on them to veto any collective action that China does not like. Hence, the Philippines may find itself doing most of the heavy lifting either with Vietnam—another major maritime claimant in the South China Sea—or even alone, given Hanoi’s dodginess about offending Beijing. Neither Brunei nor Malaysia—ASEAN’s other two countries subject to China’s maritime expansion—has demonstrated much resolve to defend their overlapping EEZs and territories.

The overall trend is positive nonetheless: ASEAN is beginning to take a more active role in addressing mutual concerns and regional threats. However, it’s clear that ASEAN members do not consider every issue equally important to their national interests, resulting in varying levels of support for collective responses. Additionally, whenever an issue involves China, as in the case of the South China Sea, the dynamic swings sharply toward less ASEAN cohesion due to the potential strategic risks that those closely aligned with Beijing might face if they go against China’s will. Ultimately, ASEAN’s deeper involvement in regional crises will likely be limited to resolving disputes among members or, as in the case of Myanmar, within one fellow member. At its heart, this is ASEAN’s founding mission anyway.