In September 1940, a group of British scientists arrived in Washington. Back home, their country was making a heroic stand against Nazi Germany, which had conquered most of the Continent and was now trying to subdue Britain from the air. The members of the delegation were hoping that they could sway the Americans to their side. But rather than resorting to moral or emotional pleas, the scientists—led by Imperial College Rector Henry Tizard—had something more concrete to offer.

There was the resonant cavity magnetron, a remarkable innovation that would soon enable Allied forces to install powerful radars on their planes and ships. One American historian would later refer to it as “the most valuable cargo ever brought to our shores.” There was also the proximity fuse, which improved the accuracy of gunnery by magnitudes. There were advanced designs for jet engines, gyroscopic gunsights, self-sealing fuel tanks, and a whole host of other useful inventions.

In September 1940, a group of British scientists arrived in Washington. Back home, their country was making a heroic stand against Nazi Germany, which had conquered most of the Continent and was now trying to subdue Britain from the air. The members of the delegation were hoping that they could sway the Americans to their side. But rather than resorting to moral or emotional pleas, the scientists—led by Imperial College Rector Henry Tizard—had something more concrete to offer.

There was the resonant cavity magnetron, a remarkable innovation that would soon enable Allied forces to install powerful radars on their planes and ships. One American historian would later refer to it as “the most valuable cargo ever brought to our shores.” There was also the proximity fuse, which improved the accuracy of gunnery by magnitudes. There were advanced designs for jet engines, gyroscopic gunsights, self-sealing fuel tanks, and a whole host of other useful inventions.

Above all else, there were revelations about the top-secret British nuclear weapons program, which they had begun before any other country. That knowledge would help to inspire the Manhattan Project, which would soon include British scientists as well as Europeans who had fled fascism before finding refuge in the United Kingdom.

Americans don’t actually hear much about the Tizard mission when they study the history of World War II. But they should. Most U.S. citizens still hold on to an overwhelmingly U.S.-centric view of the war—one that regards Britain as a weak and shaky power that was rescued in the nick of time by its mighty friends overseas. This sadly overlooks the valuable fund of knowledge that the British brought to the war effort—and which helped to lay the foundations for the United States’ postwar technological edge.

Policymakers in Washington would be well-advised to ponder the moral of 1940. Right now, U.S. discourse about assistance to Ukraine is myopic. Kyiv’s enemies in Washington love to depict it as a whiny pleader, selfishly trying to cadge more and more stuff that it needs to win the war. Yet there are actually a number of valuable lessons that the U.S. government—and especially the ossified defense establishment—could be drawing from the Ukrainians’ remarkably successful resistance to one of the world’s biggest military powers.

Now, it’s true that Ukraine doesn’t have the plethora of research institutions that Britain boasted at the end of the 1930s. Nor does Kyiv have anything like the vast U.S. industrial base today. Yet there can be no disputing that the Ukrainians have shown remarkable ingenuity in crafting their response to Russia’s invasion.

Outsiders often don’t realize that Ukraine was the heartland of the Soviet Union’s defense industry (including missile development), which created a rich legacy of engineering and scientific know-how that Kyiv still draws on today. Ukraine’s strong traditions of civic activism and creative entrepreneurship have shaped a unique culture of technological adaptiveness that I’ve described on these pages as “flat war”—one that is anti-hierarchical, cost-effective, and highly responsive to events on the battlefield.

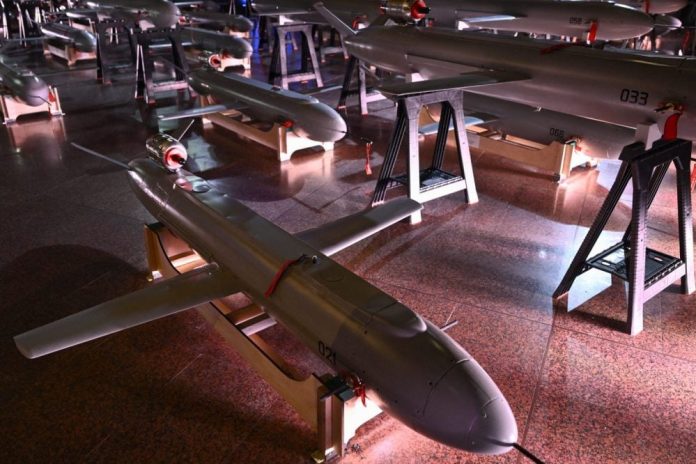

NATO planners are said to be particularly impressed by Ukraine’s Delta battlespace management system, which integrates imagery and data from a wide variety of sources into digital maps that can be easily shared across the entire military. Kyiv’s pioneering naval drones have enabled it to destroy one-third of the Russian Black Sea Fleet and drive Russian ships out of their home port in Sevastopol.

Concerned with minimizing their human losses, the Ukrainians have also been the first to make wide use of land-based robots—another development watched closely by militaries around the world. Most recently, the Ukrainians have also been integrating artificial intelligence into the targeting systems of their aerial drones; one recent report suggests that 90 percent of their drones will incorporate AI by the end of this year. And shades of 1940, they’ve also developed a new generation of proximity fuses that uses lasers or magnets to trigger explosions—systems now used widely in land mines sown by drone.

A spokesperson for a Czech defense company partnering with the Ukrainians put it well: “Ukraine is not just a recipient of aid. It is shaping modern warfare.”

The Europeans get it. The British, Germans, and Swedes are plowing billions into Ukraine’s defense industry. The Danes, who have been the most active in pursuing defense cooperation with Kyiv, are now leading a consortium that includes nine Nordic and Baltic NATO members. The Europeans are investing in the development of air defense systems, cruise missiles, loitering munitions, and Ukraine’s Bohdana self-propelled howitzer.

Are the Europeans spending all this money out of the goodness of their hearts? Not likely. They understand perfectly well that investing in what has become Europe’s crucible of military innovation will not only help Kyiv to hold off the Russian invaders but also bolster their own defenses as they desperately try to ramp up their own forces to deter the growing threat from Moscow.

They’ve also figured out that learning from Kyiv isn’t just learning about how to make cool gadgets—it’s also about leveraging Ukraine’s philosophy of flat war: the art of devising systems at a speed and price unheard of in the complacent West. As Ukrainians never tire of pointing out, they don’t just have products to offer; they have also subjected all these products to exhaustive battlefield testing and have the datasets to prove it. Some of this testing and data may end up being more valuable than the physical equipment.

No one needs to absorb these lessons more than the United States, where decades of budget largesse have created a defense industry dominated by five major corporations that hold monopoly or near-monopoly positions. These coddled behemoths specialize in political connections and the production of huge, exquisite products such as the F-35 fighter plane, which has now cost U.S. taxpayers a total of more than $2 trillion.

So it’s not hard to understand why Ukraine’s start-up mentality appeals to many politicians and businesspeople who feel that Pentagon bloat is no longer the only way to go. When Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky visited Washington in October, he was accompanied by a big delegation of his country’s defense entrepreneurs, who met with warm receptions from a host of companies.

“It is just a reality that we need Ukrainian drone tech in the U.S.,” William McNulty, a partner in the U.S. venture-capital fund UA1, told the Wall Street Journal. He’s right—and his company has invested accordingly in eight Ukrainian defense companies. Another American who gets it is former Google CEO Eric Schmidt, who has also been investing in Ukrainian defense start-ups and whose company, Swift Beat, cooperates directly with Ukraine.

Even so, breaking through U.S. complacency may be hard. A few months ago, a U.S. Army unit issued a video showing what it proudly billed as a pathbreaking experiment: Soldiers had attached a grenade to a small drone and dropped it on a target. The video immediately met a wave of ridicule, as observers quickly pointed out that the supposed achievement showcased by the U.S. Army was something that Ukrainian soldiers have been doing, in endless variations, literally uncountable times since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion.

The United States should help Ukraine, not least because Ukraine can help in return. How long will Americans need to figure that out?